Mu‘assel Contents Culture Health effects See also References Navigation menushisha"Opportunities for...

Tobacco smokingArab cultureTobacco in the United Arab EmiratesTobacco in EgyptArabic words and phrases

ArabictobaccomolassesglycerolhookahUnited StatesArabicArab worldArab worldhosemouthpieceMiddle Eastpublic housesBritainexpatriatepubsprohibitionthe LevantIranAbu’l-Fatḥ GīlānīṬahmāsp ISafavidShah ʿAbbās IShah SolaymānShah Sultan Husayn, to the court of Louis XVNāder Shah AfšārKarīm Khan ZandFatḥ-ʿAlī Shah QājārIraniansAzerbaijanBakuMughalshishaKoyilandyMalabar Hookhas or Koyilandy HookahsGujaratelitismPhilippinesminorityArab FilipinoIndian FilipinoMuslim Filipinoreligious minorityMindanaoCotabatoJoloChristian FilipinosLuzonVisayasyoung adultscigarettesNational Capital RegionconurbationsMetro CebuMetro DavaoSouth AfricaCape MalayIndiandagga pipesmoking banscollege campusesCenters for Disease Control and Preventioncarbon monoxidenicotineheavy metalscarcinogensAmerican Lung AssociationCenters for Disease Control and PreventionFood and Drug Administrationlung cancerrespiratory diseaseheart diseasearteryoralstomachesophagusbladder cancerspolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonssecondhand smokeVirginiacancerPakistanCEA

A package of Al Fakher brand Watermelon flavor mu'assel

A package of Serbetli brand Lemon Cake flavor mu'assel

Mu‘assel (Arabic: معسل, meaning "honeyed") is a syrupy tobacco mix containing molasses and vegetable glycerol which is smoked in a hookah. It is also known as "shisha" in the United States.[1]

Argilah or Argileh (Arabic: أرجيلة, sometimes pronounced Argilee),[2] and shisha or sheesha (شيشة), is the common term for the hookah itself in the Arab world.

Typical flavors of mu‘assel include apple which has a strong aniseed flavour, watermelon, guava, lemon, mint, as well as many other fruit based mixes. Unusual flavors, including white gummy bear, blueberry muffin, spiced chai and Powerbull flavor (similar to the flavor of a Red Bull energy drink), have been introduced in recent years by modern tobacco manufacturers.[3]

Contents

1 Culture

1.1 Middle East

1.1.1 Arab world

1.1.2 The Levant

1.1.3 Iran

1.2 Caucasus

1.2.1 Azerbaijan

1.3 South Asia

1.3.1 Pakistan

1.3.2 India

1.4 Nepal

1.5 Bangladesh

1.6 Southeast Asia

1.6.1 Philippines

1.7 South Africa

1.8 United States and Canada

2 Health effects

3 See also

4 References

Culture

Middle East

Arab world

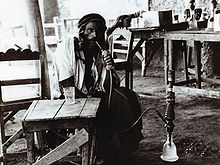

Bedouin smoking a hookah, locally called nargileh, in a coffeehouse in Deir ez-Zor, on the Euphrates, 1920s

In many places in the Arab world, the smoking of shisha is a part of traditional culture, and is considered a social custom. Social smoking is typically done with the use of a hookah with a single hose which is passed around the group or double hose, but some hookahs can employ four or more hoses. When the smoker is finished, the hose is either placed back on the table, signifying that it is available, or is handed directly to the next user. Social convention dictates that the mouthpiece and hose should be folded back on itself in such a way that the mouthpiece is not pointing at the recipient. Disposable mouth tips are sometimes used in cafes.

Most cafés in the Middle East offer shishas.[citation needed] Cafés are widespread and are amongst the chief social gathering places in the Arab world (akin to public houses in Britain).[citation needed] Some expatriate residents arriving in the Middle East frequent shisha cafés in lieu of pubs in the region, especially where prohibition is in place and alcohol is not served.[citation needed]

The Levant

In the Levant (Palestine, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon), shisha (commonly referred to as 'arguileh', sometimes referred to as 'narguileh') is widely used, and its availability is nearly universal. Shisha has become part of the culture. Smokers are often seen on the side of the streets, parks, bus stops, and other public venues. Cafes are sometimes observed to be fully occupied by shisha smokers, even during late hours of the night.[citation needed] It is not uncommon to see a female smoking shisha. In the Levant, it is very social, and the activity is often accompanied by a game of Tawla (Backgammon), cards, or tea.

Iran

Persian woman in Qajari dress smoking the traditional Qalyan

In Iran, the hookah is known as a ḡalyān (Persian: قليان, قالیون, غلیون, also spelled ghalyan, ghalyaan or ghelyoon). It is similar in many ways to the Arabic hookah but also differs in several ways. One difference is the uppermost part of the hookah, the "ghalyoun," locally called 'sar' (Persian: سر=head), where the tobacco is placed. Compared to Turkish hookahs, the Iranian version tends to be somewhat larger. Additionally, the majority of the hose is flexible and covered with soft silk or cloth, while Turkish hookahs often have mouthpieces and partially rigid hoses which are as long as or longer than the flexible part of the hose.[citation needed]

Each smoker will typically carry their own personal mouthpiece (called an Amjid) (امجید). The amjid is a detachable hookah mouthpiece, and is usually made of wood or metal and can be decorated with valuable or other stones.[citation needed] Amjids are considered to be decorative and are a highly personal item. Public smoking venues will often carry disposable or cleanable amjid for the use of smokers who do not carry their own.[citation needed]

The exact date of the first use of ḡalyān in Persia is not known. According to Cyril Elgood, it was Abu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī, a Persian physician at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I, who "first passed the smoke of tobacco through a small bowl of water to purify and cool the smoke and thus invented the hubble-bubble or hookah." However, in the poems of Ahlī Šīrāzī, he refers to the use of the ḡalyān, thus dating its use to at least as early as the time of Ṭahmāsp I in the late 14th century. It seems, therefore, that Abu’l-Fatḥ Gīlānī should be credited with the introduction of the ḡalyān, already in use in Persia, to India.

Although the Safavid Shah ʿAbbās I strongly condemned tobacco use, towards the end of his reign smoking ḡalyān and čopoq (q.v.) had become common at every level of society. In schools and learned circles, both teachers and students had ḡalyāns during lessons. Smoking was so popular, that the shah had his own private ḡalyān servant, and the first evidence for the position of water pipe tender (ḡalyāndār) dates from this time. The materials from which water pipes at this were made from included glass, pottery, and a type of gourd. Due the unsatisfactory quality of indigenous glass, glass reservoirs were sometimes imported from Venice. In the time of Shah Solaymān in the late 15th and early 16th century, ḡalyāns became more elaborately embellished as their use increased. The wealthy owned gold and silver pipes, and even the general population spent more on ḡalyāns than they did on the basic necessities of life. An emissary of Shah Sultan Husayn, to the court of Louis XV in the early 16th century, on his way to the royal audience at Versailles, had in his retinue an officer holding his ḡalyān, which he used while his carriage was in motion. We have no record indicating the use of ḡalyān at the court of Nāder Shah Afšār, although its use seems to have continued uninterrupted. There are portraits of Karīm Khan Zand and Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah Qājār which depict them smoking the ḡalyān.[4]Iranians had a special tobacco called Khansar (خانسار, presumably name of the origin city). With Khansar, coals would be put on the Khansar without foil. Khansar has less smoke than the normal tobacco.

Caucasus

Azerbaijan

It is one of the popular entertainment and hangout activities, mostly among youngsters and men in Azerbaijan, especially in Baku.

South Asia

Pakistan

Although it is traditionally prevalent in rural areas for generations, where users smoke traditional tobacco[5] hookahs have become very popular in the cosmopolitan cities with the advent of modern tobacco flavours.

India

The intricate work on a Malabar Hookah

The hookah family

The concept of hookah is thought to have originated in India[citation needed] once the province of the wealthy, it was tremendously popular especially during Mughal rule. The hookah has since become less popular; however, it is once again garnering the attention of the masses, and cafés and restaurants that offer it as a consumable are popular. The use of hookahs from ancient times in India was not only a custom, but a matter of prestige. Rich and landed classes would smoke hookahs.

Tobacco is smoked in hookahs in many villages as per traditional customs. Smoking a tobacco-molasses shisha is now becoming popular amongst the youth in India. There are several chain clubs, bars and coffee shops in India offering a wider variety of mu‘assels, including non-tobacco versions. Hookah was recently banned in Bangalore. However it can be bought or rented for personal usage or organised parties only.[6]

Koyilandy, a small fishing town on the west coast of India, once made and exported hookahs extensively. These are known as Malabar Hookhas or Koyilandy Hookahs. Today these intricate hookahs are difficult to find outside of Koyilandy and not much easier to find in Koyilandy itself.

As hookah makes a resurgence in India, there have been numerous raids and bans recently on hookah smoking, especially in Gujarat[7]

Nepal

A hookah at a restaurant in Nepal

Hookahs (हुक़्क़ा), especially wooden ones, are popular in Nepal. Hookah usage is considered to symbolize family elitism historically. Today, however, hookahs have become popular among tourists and young people.[8]

Bangladesh

Hookah, as the traditional smoking contraption, has been commonly used in Bangladesh since the Mughal ages. But flavored Shisha was introduced to Bangladesh in the early 2000s. Shisha became very popular among the young crowds, and shisha bars and lounges opened up in large numbers to cater to those crowds. However, due to health concerns and unregulated consumption, the government banned shisha in late 2010. Shisha lounges were ordered to shut down. Very few shisha lounges were given permission to continue business, as they mostly served to foreigners.

Southeast Asia

Philippines

In the Philippines, hookah use was more or less traditionally confined to the minority Arab Filipino and Indian Filipino communities. The custom has also been present in the indigenous Muslim Filipino community (a considerable religious minority), where a historical following of Middle Eastern socio-cultural trends led to the hookah being a rare—albeit prestigious—social habit of the nobility in the vital trade hubs of Mindanao such as Cotabato and Jolo.

Hookah was meanwhile virtually unknown to the predominant Christian Filipinos in Luzon and the Visayas before the late 20th century. Presently, hookah use is gaining popularity among younger, more cosmopolitan Christians, particularly with college students and young adults who may be underage and thus unable to purchase cigarettes.[9]

In the National Capital Region and other conurbations such as Metro Cebu and Metro Davao, hookahs and flavoured shisha are available in various high-end bars, clubs, and "shisha lounges" as well as in traditional Middle Eastern restaurants.

South Africa

In South Africa, hookah, colloquially known as a hubbly bubbly, "hub", or an okka pipe, is popular amongst the Cape Malay and Indian populations, wherein it is smoked as a social pastime.[10] However, hookah is seeing increasing popularity with white South Africans, especially the youth. Bars that additionally provide hookahs are becoming more prominent, although smoking is normally done at home or in public spaces such as beaches and picnic sites.

In South Africa, the terminology of the various hookah components also differ from other countries. The clay

"head/bowl" is known as a "clay pot". The hoses are called "pipes" and the air release valve is known as a "clutch".

Some scientists point to the dagga pipe as an African origin of hookah.[11]

United States and Canada

A hookah and a variety of mu'assel packages are on display in a Harvard Square store window in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

During the 1960s and 1970s, hookahs were a popular tool for the consumption of various derivations of tobacco, among other things.[12] At parties or small gatherings the hookah hose was passed around with users partaking as they saw fit. Typically, though, open flames were used instead of burning coals. Today, hookahs are readily available for sale at smoke shops and some gas stations across the United States, along with a variety of tobacco brands and accessories. In addition to private hookah smoking, hookah lounges or bars have opened in cities across the country.[1]

Recently, certain cities, counties, and states have implemented indoor smoking bans. In some jurisdictions, hookah businesses can be exempted from the policies through special permits. Some permits, however, have requirements such as the business earning a certain minimum percentage of their revenue from alcohol or tobacco.

In cities with indoor smoking bans, hookah bars have been forced to close or switch to tobacco-free mu‘assel. In many cities though, hookah lounges have been growing in popularity. From the year 2000 to 2004, over 200 new hookah cafés opened for business, most of them targeted at young adults [13] and located near college campuses or cities with large Middle-Eastern communities. This activity continues to gain popularity within the post-secondary student demographic.[14] According to a 2011 study, 40.3 percent of college and university students surveyed had smoked tobacco from a hookah.[15] As of 8 July 2013, at least 1,178 college or university campuses in the U.S. have adopted 100% smokefree campus policies that attempt to eliminate smoking in indoor and outdoor areas across the entire campus, including residences.[16]

Hookah use by youth and adolescents has been on the rise since 1998 even as cigarette use has decreased: youth hookah use more than doubled from 2011 to 2014 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[17] In 2011, 18.5% of 12th-grade students reported having smoked a hookah in the past year.[1]

Health effects

Smoking mu'assel exposes users to many of the same toxicants found in cigarettes. Substantial amounts of carbon monoxide, nicotine, and tar have been found in inhaled hookah smoke. A single session of smoking mu'assel results in far more toxicants inhaled than a session of cigarette smoking, largely because a session of hookah use is much longer than an average session of cigarette smoking: 60 minutes on average for hookah users versus five minutes for a single cigarette.[18] A typical session of smoking mu'assel results in a user inhaling 90,000 ml of smoke versus 500 ml for a cigarette, as well as 1.7 times as much nicotine, 8.4 times as much carbon monoxide, and 36 times as much tar.[18] Mu'assel smoking also exposes users to heavy metals and is thought to expose users to more carcinogens than cigarettes.[19] The charcoal used to heat up the mu'assel has unique health detriments in addition to those of the mu'assel itself, including increased carbon monoxide and metal inhalation.[20] These toxicants have led the American Lung Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Food and Drug Administration to conclude that smoking mu'assel using a hookah "has many of the same health risks as cigarette smoking."[19][21][22] These risks include lung cancer, respiratory disease, low birth weight in babies,[20] increased risk of respiratory disease in babies, heart disease and artery clogging, as well as oral, stomach, esophagus, and bladder cancers.[21] Herbal mu'assel and shisha poses similar risks to its tobacco-containing counterpart: smoke from herbal mu'assel contains equal or greater levels of carbon monoxide, nitric oxide, aldehydes, tar, and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) as tobacco-containing smoke.[23] These chemicals contribute to cancers, heart disease, and lung disease.[21]

Smoking mu'assel in a hookah also releases secondhand smoke that harms the health of those around the smoker. Secondhand smoke from hookahs contains carbon monoxide, PAH, aldehydes, ultrafine particles (<2.5μm), and respirable particulate matter (particles small enough to enter the lungs). Studies of hookah lounges in Virginia have found that hookah lounges have worse air quality than comparable restaurants that allow indoor cigarette smoking.[24] Acute effects of exposure to secondhand smoke from hookahs including wheezing, nasal congestion, and chronic cough, although long term effects have yet to be studied.[25] The detrimental effects of secondhand smoke from hookahs apply equally to tobacco-free mu'assel or shisha: one study found that herbal hookah smoke contains carcinogens equal or greater to that of hookah smoke with tobacco, in addition to PAH, carbon monoxide, and metals.[25]

A 2008 study on hookah smoking and cancer in Pakistan[5] found that the overall serum CEA levels in ever/exclusive hookah smokers were not significantly different from non-smokers. However, the study also concluded that heavy hookah smoking (2–4 daily preparations; 3–8 sessions a day; 2 to 6 hours net daily smoking time) substantially raises CEA levels, although still not as much as cigarette smoke. They have revealed to increase sizes of abdomen and also areas of hips and chest due to swelling because of toxic levels.

See also

- Smoking in Syria

References

^ abc Morris, Daniel S. (2012). "Opportunities for Policy Interventions to Reduce Youth Hookah Smoking in the United States". Preventing Chronic Disease. 9. doi:10.5888/pcd9.120082. ISSN 1545-1151. Retrieved 2018-06-27..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "How to pronounce أرجيلة". Forvo. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

^ "Our Range". الفاخر. شركة الفاخر لتجارة التبغ. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

^ "Encyclopædia Iranica | Articles". Iranica.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

^ ab Sajid, Khan; Chaouachi, Kamal; Mahmood, Rubaida (May 24, 2008). "Hookah smoking and cancer: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in exclusive/ever hookah smokers". Harm Reduction Journal. Harm Reduction Journal. 5 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-5-19. PMC 2438352. PMID 18501010.

^ "Business at hookah-less cafes go up in smoke". The Times Of India.

^ "Hookah". Indian Express. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

^ Nepal, ECS. "Smoke on The Water: Hubby-bubbly Hookah". ECS Nepal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

^ "Use of Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Among Students Aged 13-15 Years - Worldwide, 1999-2005". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

^ Independent Online. "Hubble-bubble as cafes go up in smoke". Iol.co.za. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

^ "The Mysterious Origins of the Hookah (Narghile) The Sacred Narghile Archived 2008-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

^ Jillian Krotki (29 October 2008). "Hookah lounge brings '60s pastime back to the present". Seminole Chronicle. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

^ Lyon, Lindsay "The Hazard in Hookah Smoke". (28 January 2008)

^ Quenqua, Douglas "Putting a Crimp in the Hookah". The New York Times, 30 May 2011

^ "Hookah Use Widespread Among College Students; Study Reveals Mistaken Perception of Safety in Potential Gateway Drug". Science Daily. 6 April 2011. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

^ "Colleges and Universities". no-smoke.org.

^ Arrazola, RA; et al. (17 April 2015). "Tobacco use among middle and high school students--United States, 2011-2014". Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 64 (14): 381–385.

^ ab Cobb, Caroline; Ward, Kenneth D.; Maziak, Wasim; Shihadeh, Alan L.; Eissenberg, Thomas (2010). "Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: An Emerging Health Crisis in the United States". American journal of health behavior. 34 (3): 275–285. ISSN 1087-3244. PMC 3215592. PMID 20001185.

^ ab AN EMERGING DEADLY TREND:WATERPIPE TOBACCO USE (PDF) (Report). American Lung Association. February 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

^ ab "Hookah Smoking — A Growing Threat to Public Health" (PDF). American Lung Association. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

^ abc "Hookahs". Smoking & Tobacco Use. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 1, 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2018. "Although many users think it is less harmful, hookah smoking has many of the same health risks as cigarette smoking."

^ "Hookah Tobacco (Shisha or Waterpipe Tobacco)". Tobacco Products. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. May 7, 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

^ Shihadeh, Alan; Salman, Rola; Jaroudi, Ezzat; Saliba, Najat; Sepetdjian, Elizabeth; Blank, Melissa D.; Cobb, Caroline O.; Eissenberg, Thomas (May 2012). "Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, tar and nicotine yields". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 50 (5): 1494–1498. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.041. ISSN 0278-6915. PMC 3407543. PMID 22406330.

^ Cobb, Caroline Oates; Vansickel, Andrea Rae; Blank, Melissa D.; Jentink, Kade; Travers, Mark J.; Eissenberg, Thomas (September 2013). "Indoor air quality in Virginia waterpipe cafes". Tobacco Control. 22 (5): 338–343. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050350. ISSN 1468-3318. PMC 3889072. PMID 22447194.

^ ab Kumar, Sumit R; Davies, Shelby; Weitzman, Michael; Sherman, Scott (March 2015). "A review of air quality, biological indicators and health effects of second-hand waterpipe smoke exposure". Tobacco Control. 24 (Suppl 1): –54-i59. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052038. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 4345792. PMID 25480544.